Centrist Strategy and the Art of Revisionism

A long overdue polemic with the Fraccion Trotskista, taking on in depth their revision of Trotskyism in their major theoretical book: Socialist Strategy and Military Art.

A Polemic with the FT, the Theoretical Heirs of Nahuel Moreno

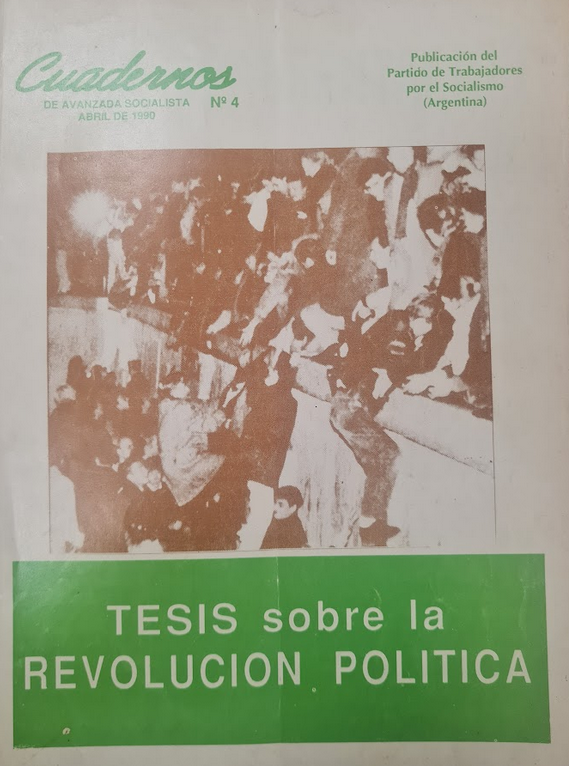

The Trotskyist Fraction has its origins in a 1988 split that announced the beginning of the dissolution of the Argentina MAS (Movement towards Socialism) and the international organization (LIT) that Nahuel Moreno built. Of all the parties spun off from that process of dissolution, the PTS and the FT have presented themselves as the most critical of Moreno’s political legacy and deny that they are Morenoites. This act of reinvention, renouncing their past history to better rearm themselves for new political turns, is perfectly consistent with the political core of Moreno’s own practice. [1]

Moreno often reinvented his own politics and in even more significant ways – entryism in the Peronist Movement, hailing the OLAS and Che Guevara, an embrace of social democratic politics – alongside a long list of twists and turns driven by political expediency nationally and internationally. This creates a number of significant problems for those who claim to uphold his legacy – which Moreno do they uphold? 1955? 1968? 1972? 1982? Pick any of those years and you can find a set of politics at odds with and contradictory to any of the others.

Moreno combined this with a pattern of pretend orthodoxy abroad and opportunism at home which would characterize all the major Morenoite internationals. There is a consistent pattern of a more opportunist mother party commanding the international sections which are forced to tack left to compete with whatever the local dominant strains of pseudo-trotskyism are. The Brazilian MRT has often posed to the left of the PSTU in Brazil, while in Argentina the Argentine PSTU presents itself as a left critic of the FIT.

The Fraction Trotskista sells an image abroad of the PTS and its electoral interventions which is far to the left of the actual day to day practice which anyone living in Argentina would be familiar with. If however the visiting foreign militants of the FT were to stay in Argentina long enough, many would find that their own politics are not so close to the PTS as they might imagine.

Abandoning the weight of Moreno’s “theoretical” legacy has allowed the FT to be the most dynamic of the Morenoites locally and internationally. Moreno’s greatest students understood that they could only ascend to take his place by striking down their old master. They began this with the advantage of hindsight in Manolo Romano’s 1994 Polemic with the LIT and The Theoretical Legacy of Nahuel Moreno.[2] It was of course considered entirely unnecessary to engage with or reference those within the Trotskyist movement who had been criticizing Moreno’s revisionism for decades.

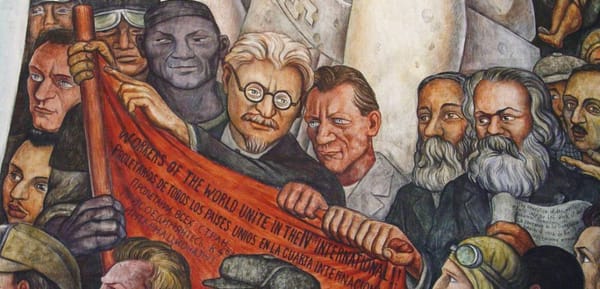

In this article they compare Moreno’s most flagrant revisionism of the Trotskyist program with Trotsky’s writings. They criticized most of the content of the Actualización del Programa de Transición. They also criticized the slogans of the LIT in East Germany and the other worker states for having limited themselves to democratic demands; but also for not taking seriously enough the national struggles for independence. They highlight a concept – more or less robbed from Moreno (who robbed it from Lambert) – which was to become a cornerstone of their understanding of the post-WWII world and plays a star role in Socialist Strategy and Military Art, “The Order of Yalta”. A supposed counter-revolutionary alliance between Imperialism and the Stalinist bureaucrats.

Even in 1994, after the fall of the USSR, this perspective combined with their obsession around tailing nationalist struggles led them to absurd political conclusions: for the FT in this article, Serbia’s Milosevic was “endorsed by US Imperialism” in his war against Bosnia. US Imperialism as we all know had a very different perspective when it launched its relentless bombing campaigns. Even FT cadre will admit that the article is in many ways “outdated”, however while the FT is happy to criticize the dead Moreno it has never dared to openly criticize the positions formulated by the FT since its formation. A contradiction which will become flagrantly apparent in Socialist Strategy and Military Art when Albamonte and Maiello review the fall of the USSR.

This formal break from Moreno does pose an important question for the FT: if they had all been formed as cadres in a fundamentally revisionist political current, how do they justify their claim to revolutionary leadership? The answer for the FT is of course that every other Trotskyist political current must have degenerated. Albamonte in another of the FT’s defining texts claimed that “shortly after the period of 1951-1953 the Fourth International became a centrist movement, where the common denominator of its main tendencies was having lost the strategic orientation of an independent revolutionary party”.[3] Bare threads of revolutionary continuity do exist and Albamonte claims to have one, but really everyone degenerated. We are all guilty of losing our “strategic orientation”.

This focus on “Strategic Orientation” is where the book Socialist Strategy and Military Art will pick up as it weaves together the theoretical and programmatic development of the Fraction Trotskista.

The starting point of the book is the reconstruction of the importance of Clausewitz as a military strategist and as a strategic inspiration for Lenin and Trotsky – a task with which they begin in order to set out a far more ambitious objective to “re-establish the unity of the Marxist Program and Revolutionary Strategy. Only in this way can the relation between strategy, marxism and military questions be brought back to its rightful place”.[4] Clausewitz himself is invoked and studied much in the same way as he was invoked by Kautsky, Lenin and the other partisans of debate within the 2nd international – a scaffold around which a political and strategic debate took place. Here as then, Clausewitz finds himself the continuation of politics by other means.

The book is simultaneously an academic work, a programmatic exposition and a historical account. It is as a programmatic exposition of the FT’s most complete account of their interpretation of Trotskyism and as a historical reconstruction (or deconstruction in this case) of revolutionary continuity that we will concentrate our critique here. Socialist Strategy and Military Art consolidates what has been a nebulous and undefined theoretical tradition of the FT into a concentrated body which can be subject to a clear Trotskyist critique. It also helpfully marks out as early as the prologue some of the final destinations which these theoretical formulations are designed to justify.

Final Destinations: Egypt, Greece, Brazil

The book opens with a flurry of academic citations and quotes: Carl Schmitt, Laclau and Mouffe, Foucault, Giorgio Agamben, Alain Badiou alongside left references to Bensaid, Antonio Negri, Alex Callinicos and others. These are mostly adornments, totems designed to attract the support of graduate students and ward off the unprepared reader from challenging the fundamental content within. Do not be distracted by the illustrations proclaiming “Here be Dragons” and focus instead on the actual cartography.

The course which the FT charts here is a proper Odyssey which passes through Egypt and Greece only to be spit out and shipwrecked on the coasts of Brazil. In their absorption of Gramscian categories Egypt becomes the “Eastern” and Greece the “Western” example of revolutions which were ultimately derailed. In Egypt the FT once polemicized against the Revolutionary Socialists (IST) call to vote for Morsi in the second round,[5] rejecting the stageist approach which RS used to justify this out of their fear of the military. An interesting position for a current which was a few years after to justify voting for Haddad in Brazil out of fear of Bolsonaro.

The focus of Albamonte and Maiello is on Greece. Greece and SYRIZA is important, as it was once the basis for much of the FT’s left appeal. Whereas most of the world pseudo-trotskyist left was chasing after SYRIZA, actively participating in it, calling to vote for it and even working to export the model abroad, the FT criticized those who spread illusions in a “Left Government” and especially the USEC and other currents[6] efforts to paint it as an extension of the Workers Government tactic:

In this way the US transforms a tactic designed to accelerate the experience of the masses with reformist leaderships, in situations of acute class struggle, into electoral support for candidates and programs of class collaboration.[7]

However there is a noticeable and important turn present in the book. They no longer criticize SYRIZA in those same terms, as the “Government of the Left” being an excuse for “electoral support to candidates and programs of class collaboration.” The discontinuity here is important to point out because the FT has abandoned its opposition to voting for candidates and programs of class collaboration – Haddad in 2018 Brazil and Boric in 2021 Chile are the most obvious cases – but not the only ones. Though they have never acknowledged or justified the turn, the fact is the FT was once opposed to voting for candidates and programs of class collaboration, and now they are not. The rightward drift of the FT towards reformism means that they also have to reinvent and reinterpret their own left posturing around Greece.

Albamonte and Maiello focus on the inability in Greece to constitute a United Front – but don’t detail what exactly they would conceive this United Front as being around. The essence of the United Front is to march separately, strike together – not as the FT have reinterpreted it to justify permanent electoral propaganda blocks – march together. Considerable sectors of the world-left which trailed after SYRIZA cried endlessly about the KKE’s (Greek Communist Party) principled refusal to form a co-government with SYRIZA. There are however very real, and very relevant criticisms of its refusal to form a united front around key worker and anti-fascist struggles.

They criticize (as many left supporters of Syriza did easily enough) the coalition with the right nationalist ANEL party. Their main jumping off point however is the referendum:

The overwhelming result of the referendum against austerity and the Troika was a huge missed opportunity to reverse that dynamic, one in which their could have been a fundamental role for the tactic of a “workers government”. A workers government in Greece in 2015 could have taken advantage of the will expressed in the referendum in order to impose base measure of self defense against the pass towards “direct action” by the big banks and the Troika through capital flight - something which, as Kouvelakis underlined himself, drastically changed the relation of forces - and on this basis implemented the refusal to pay the external debt. We could also say this in respect to the 30% of businesses which closed and could have been expropriated under workers control, among other resolutions.[8]

The referendum was - and only could be given it was called directly by Tspiras for that purpose - a gesture intended to shore up the negotiating capacity of Tsipras before the banks. The duty of communists was to announce and fight against the impending betrayal which it necessarily implied.

They instead want the referendum to have been the jumping off point for their vision of a “Workers Government”. A “Workers Government” with SYRIZA? They leave it ambiguous as to what form this would take. They take up the debate between Callinicos and Kouvelakis to say that neither was correct. This is the arithmetic they weave: the left platform in SYRIZA had the power to do something and didn't, Antarsya didn’t have the forces to intervene substantially and so offered no real alternative.

“Now of course, without a doubt the first condition for a dynamic like this is the constitution of a material force capable of influencing events and constructing a revolutionary alternative to the neo-reformist Syriza. Without this, following the logic explained by Kouvelakis, the Left Platform – which constituted 30% of the organization – by mid 2015 was reduced to insignificance. However even those who did plant this, like the anti-capitalist Left Coalition, Antarsya, the main alliance to the left of Syriza and the CP, lacked material force or significant influence.

The greek experience shows the need for strategic work so that in the decisive moments the result is not already determined by the impotence and/or inexistence of a revolutionary alternative”[9]

The parliamentary focus of this analysis is notable: SYRIZA after all never had a significant militant base in the key sectors of the working class even as it briefly convinced many to vote for it. The subsequent collapse of “Popular Unity”, the left SYRIZA opposition, is a clear demonstration of how ephemeral that “material force” was. The decisive battleground in Greece was not in parliament or in the ballot boxes of the referendum, it was in the workplaces. Genuine Trotskyists called for action by the working class towards this end, compare the position laid out by the League for the Fourth International:

The League for the Fourth International says that the only way to defeat the bankers’ diktat and put an end to the devastating austerity program of the Eurobosses is by mobilizing the workers’ power on the road to a socialist revolution in Greece and throughout Europe. To stop the financial extortion, workers should occupy the banks and place them under control of elected workers commissions against the Eurobankers and the Greek capitalist government. Against the threat of privatization, workers in the ports of Piraeus, Thessaloniki and the Greek islands should occupy the ports (and airports)and place them under workers control. Make public health and public transportation permanently free, under workers control. As for the unpayable foreign debt, the workers should repudiate (cancel) it entirely, as the Russian workers did in October 1917. But that will take a revolution.[10]

The real sectarianism of the KKE was not in parliament – where they drew a minimum line of class independence against SYRIZA. It was in the unions where they worked tirelessly to prevent any real united front actions to smash the fascist Golden Dawn or to launch a serious general strike which would pose the question of workers power in Greece. The “Material Force'' necessary in Greece was an embedded leninist-trotskyist party capable of disputing the KKE’s leadership of the working class and fighting for socialist revolution. That Albamonte and Maiello see “Material Force” in the pathetic “Left Platform” reformists is a testament to how deeply their political vision has degenerated under the influence of their pursuit of legislative banks for the Left and Workers Front (FIT) in Argentina.

The real meaning of their attention to the “Material Force” of Left Platform reveals itself when they step away from Greece and come closer to home, where they have had a real chance to intervene and apply their new political line:

This is not just about Syriza or Podemos. For example, at the end of 2016 in the middle of a crisis of the PT, the Party for Socialism and Liberty (PSOL) in Brasil, with Marcelo Freixo at its head, was fighting to win the municipal government of Rio de Janeiro, one of the most important cities of Latin America, which had seen great process of teacher, worker and student struggles. What would PSOL have done if it had won that election?

Their declared intention of agreements with businessmen, their plan to respect the Law of Fiscal Responsibility, etc. all make it seem like they would take a path similar to Syriza. However, the movement expressed in the vote in Rio planted the possibility of an alternative path of rupture with capitalism, where the city would transform into a revolutionary bastion for the rest of the country. This second alternative returns us to the problems of strategy and tactics, to the modification – rather than administration – of the relation of forces.[11]

This small tidbit in the prologue is extremely significant. Today, it sounds like a particularly ambitious editorial from Jacobin endorsing Mamdami’s campaign in New York. Jim Robertson, a founder of the International Spartacist Tendency, was fond of stating that program generates theory. Given the FT’s preference for debating with academics over Trotskyists, we can suggest Umberto Eco’s famous phrase that ideas are “like a ladder, built to attain something”. Theoretical production generally exists to justify political ends. This shocking formulation around Freixo’s police socialist, bourgeois campaign is in effect the sort of political end which the rest of the book serves to justify. Strategy will be taken by Albamonte and Maiello on a world tour, but its final destination is nothing less than a justification for what Trotsky once derided as efforts by left centrists to “peddle their wares in the shadow of the Popular Front”. As such it requires special attention not only to the event itself, but the political context set in the Brazilian section of the FT which brought it to such a point.

The FT in Brazil - Centrist and Reformist Zigzags

Rio de Janeiro is where Albamonte and Maiello choose to make their stand in the prologue, and we’re happy to take up the FT on their chosen terrain. It is where the FT’s politics have left the most visible wreckage on its veering path from Centrism into an open embrace of reformist politics.

As an exercise here it will be useful to explain the character of PSOL entirely in the words of the FT’s Brazilian section. The Archives of Palavra Operario, the newspaper of the LER-QI, have been essentially scrubbed from the internet. Awfully convenient given the vast political turn that was implemented around the time Palavra Operária turned into Esquerdia Diario and the LER-QI became the MRT. A happy accident perhaps. However it is still possible to see in some of the pages of Estrategia Internacional, the old theoretical journal of the FT, the analysis which they once maintained around PSOL.

In a 2012 article[12], they denounce PSOL for having formed open electoral coalitions with bourgeois and even right-wing parties like the PSDB, DEM, PMDB, PDT as well as the PT itself. They reject the PSTU’s characterization of PSOL as even being a workers party or a socialist party, instead marking it out as a “reformist party with a petty-bourgeois social base”. The pseudo-trotskyist currents like the MES and CST which performed long term entryism into PSOL were guilty of “liquidating themselves as Trotskyist traditions”. They had clear and harsh words for the PSTU’s tailing of PSOL:

The leadership of the PSTU continues with their “permanent tactic” of building fronts with reformists and conciliators, “compromises” which are, in truth, popular front politics. They think that just because there is no direct bourgeois party in the “agreement” that it can’t be considered as such.[13]

The LER-QI was also quite active discussing and denouncing the most prominent example of a PSOL government – in the City of Macapa, Clecio Luis triumphed as PSOL’s candidate backed by alliances with bourgeois parties and with bourgeois money. The FT wrote the following analysis of this experience in 2014:

In Macapa, capital of the state of Amapa, PSOL was elected in 2012 as part of a broad coalition which included the Communist Party of Brazil (PCB) and which had the support of the Democratic Party (DEM) and the PSB. Currently it governs together with a huge variety of bourgeois parties, respecting the so-called “law of fiscal responsibility” which obliges governments to put off social needs in order to guarantee the payment of interest and debt to big millionaires and international investors. To this end, they used the municipal guard to repress teachers who went on strike for better salaries and to defend education.[14]

Did the original election of Clecio Luis have a “movement which was expressed in the vote” like what Albamonte points towards in order to justify the FT’s approach to Freixo’s quite similar campaign? Reduced to such vague terms, any vote, especially a winning one, necessarily expresses some amount of movement – at the very least from one's house to the polls. The final destination – a left face on the repression of striking teachers – was however easily predictable on the basis of PSOL’s reformist program and politics.

By the time of Frexio’s 2016 campaign in Rio de Janeiro however a number of significant political transformations had taken place within the party formerly known as the LER-QI, the MRT.

In 2015 the Argentine leadership of the FT grew impatient with the rate of growth and development of the Brazilian section and conversations were opened with its leadership on a “Strategic Impasse” at which it had arrived. The inability of the newly renamed MRT to project itself at the electoral level and construct “public figures” with national visibility posed the risk of degenerating as a tendency which was only capable of witnessing revolutionary crisis and not intervening decisively in one.

This went hand in hand with an analysis at the international level by the FT leadership that there was a “risk of sectarian degeneration for the latin-american groups of the FT”. An analysis that came out of the 9th International Conference of the FT held in May 2015 – and given its sweeping character, it’s safe to say that it came straight from the leaders of the PTS. The golden child of the FT at this moment was the French section – which had built itself through entryism into the NPA and was finding luck picking up militants who rejected the open liquidationism of the NPA leadership and who saw in SYRIZA an important betrayal of class politics.

An accusation of “sectarian degeneration” in the correct use of the term is not unwarranted, the LER-QI’s 2013 betrayal in the Sao Paulo subways[15] where they didn’t vote for a strike, was indeed a “sectarian” betrayal and degeneration. However, what the leadership of the FT meant by sectarian was what all Centrist political leaders meant by it – too close to the political principles of Trotskyism. This was the moment of the Del Cañoification of the international parties of the FT. The global adoption of a strategy focused on artificially producing “media figures”, electoral maneuvering and prioritizing the likes and views of web articles. Put the copies of Cannon’s History of American Trotskyism away and get into the digital trenches around the real pressing issues for the proletariat, like the latest albums by Britney or Shakira.

The application of this “NPA turn” in Brazil meant a 180 degree turn on the FT’s analysis of PSOL and opened up a controversial debate within the LER-QI/MRT on adopting a tactic of entryism in PSOL. According to the leadership, examples like the government in Macapa could be ignored because they were “marginal local governments” although it was mentioned that if PSOL won more central mayorships AND if this changed “how the party is seen nationally” then this COULD invalidate the strategy. Here the potential of a Freixo campaign in 2016 in Rio was actually mentioned as a possibility of just such a change. The same excuse of “marginality” was made for PSOL’s coalitions with bourgeois parties. Couched in hard terms, making allusions to the experience of the French Turn in the 30s and with a few expulsions or drop outs along the way, the PSOL turn was adopted by the Congress.

The Argentine leadership was of course happy with this. In a July 2015 letter to the organization, they expressed their excitement with the fact that the article asking for entry in PSOL had accumulated “two thousand likes”. Requesting to join a party that shortly before they had been denouncing as class collaborationist apparently also meant that “certainly we will seem much more serious and as a far better alternative to the workers and students who sympathize with our program and politics”. If Facebook likes are your marker for political influence and your “seriousness” is expressed in your willingness to dramatically turn your back on years of previous critiques ... you might want to consider a career in digital marketing over revolutionary leadership.

The reformist leaders within PSOL saw right through the MRT – many of them were pseudo-trotskyists themselves of course who knew well what that kind of entryism could imply – and a combination of delays and rejection left the MRT in the awkward position of effectively carrying out political entryism from without as they were excluded from formally becoming members of PSOL.

This is the context in which the MRT’s participation in Freixo’s campaign for mayor of Rio de Janeiro takes place and which Albamonte here transforms into a model.

The Freixo Campaign

Marcelo Freixo made his name in politics as a state deputy in 2008 by opening up and leading an investigative commission into the role of the militias – criminal organizations in the favelas run by off-duty police officers and firefighters. His proposals here included raising police salaries, improving their training, tighter judicial control over the police, harsher punishment for the crimes involved in the militias, federal police oversight of… police corruption, a number of judicial and fiscal reforms, as well as two very significant proposals:

34. Set up in Rio and other municipalities, with the participation of the Municipal Guard, a politics for the ostentatious presence of police in neighborhoods and areas with the highest incidence of crimes, calling on community representatives and local commercial associations, taking away space from illegal security;

35. In the same sense, redistribute the police personnel, principally military personnel, having as basic criteria the rates of crime (proportion between number of crimes and the population in the area);[16]

These two proposals for a heavier police presence were in their own way taken and implemented by the government of Rio de Janeiro with its program of UPPs: Units of Pacifying Police. These saw the massive deployment of police in overwhelming force to Favelas in locations strategic for tourism and industry. This deployment came hand in hand with a vicious campaign of racist terror, torture and murder – one of the most significant cases being that of Amarildo Dias de Souza in 2013, a black bricklayer from Rocinha disappeared by the police.

This wasn’t just an incidental product of his report, Freixo has always had a consistent line on the police. The 2016 campaign was Freixo’s second attempt to campaign for Mayor. In the lead up to his first, in a 2011 interview, he gave his thoughts on the role of the police in Rio arguing that the “Look, I always defended community policing. I think that the principle of police presence is unquestionable.” For Freixo the main problem was that the police “should be more valued with salaries and training… the salary is absurdly low, training is very precarious. And there needs to be some control over the police.”[18]

Back in 2011, in the LER-QI’s period of risking “Sectarian Degeneration”, they were able to recognize this position of Freixo and link it beyond him to the general character and objectives of PSOL:

Marcelo Freixo is the main voice of the PSOL in politics around human rights and violence. However his position are not individual and are a distillment, specifically, of the general line of his party: humanize the institutions of capitalism and brazilian bourgeois democracy. The PSOL nationally became known for its position of CPIs where they tried to “purify” parliament of its corruption, same as they try to do with the UPPs and CPIs around the militias. They want to improve the “democratic state of laws” (as they call it), believing that in this way the state’s class interests will be overcome and will become “public”.

We affirm the opposite! The so called “democratic state” is a mask for the bourgeois state. Its institutions need to be destroyed. Its repression cannot be humanized, it must be abolished![19]

Humanizing and purifying the institutions of the Brazilian bourgeoisie is an accurate characterization of the general political objective of Freixo and the PSOL as a whole. Freixo in 2014, even in the aftermath of protests against the disappearance of Amarildo, largely defended the basic principle of the UPPs, only wishing that they were better integrated with communities as he explained in an interview with El Pais:

The idea that the police should be present instead of entering, making war and leaving, is naturally valid. All societies need police, but no society only needs police. Rio needs a project of the city for the favelas. The police need to serve those residents, instead of controlling them.[20]

In the same interview he criticized the fact that the UPP’s were mostly concentrated in strategic areas and that they weren’t present in favelas run by the militias. For Freixo, effectively an honest bourgeois reformer, the fundamental problem was one of having better paid, better trained, more transparent police subject to one or another form of “community control”.

Freixo has been nothing if not consistent in his positions around the police and his proposals – in the context of Brazil being an honest reformer of the bourgeois state has made him a target – but there is nothing here that would make him into the leader of “an alternative course of rupture with capitalism, where the city is transformed into a revolutionary bastion for the rest of the country”.

In 2015 Freixo restated his position on the police with the peculiarity that it was declared… IN AN INTERVIEW PUBLISHED UNCRITICALLY BY ESQUERDA DIARIO. Here in his brief comments he declared “The state must understand that it cannot just have police, the police have to be different”.[21] Not even a critical comment was left afterwards by Esquerda Diario to challenge Freixo’s clear and well known pro-police politics.

In 2016 Marcelo Freixo running under the label of PSOL, a “class collaborationist” party which had previously unleashed police on striking teachers, managed to capture the support of wide sectors in Rio de Janeiro who rejected the conservative and corrupt politics of Crivella, the leading right wing candidate. He made it to the run-offs and though at a great disadvantage, it was not impossible to think he could win. He worked to calm Rio’s bourgeoisie with a symbolic “Open Letter to Cariocas”, copying Lula’s “Open Letter to the Brazilian People” and offered a similar commitment to disciplined, fiscally responsible capitalist governance.[22]

In 2016 however the MRT offered clear support for Freixo’s campaign, declaring that it “Shows the disposition to resist of broad sectors. Freixo positioned himself against the coup, hasn’t received money from businessmen, has not made alliance with bourgeois parties and not even formal ones with the PT or PCdoB. He has positioned himself clearly as a defender of the oppressed sectors, as well as defending a series of workers rights like with the struggle now against the PEC 241.”[23] After describing the reactionary politics of his opponent Crivella, Esquerda Diario declared “For this reason, we are accompanying the movement which struggles for the victory of Freixo”.[24]

Freixo did reject open coalitions and campaign financing from business, but this doesn’t make his pro-police campaign – which the same article by ED even mentions clearly by citing a Military Police Officer’s endorsement of his campaign – anything other than a run of mill “progressive” expression of “sewer socialism”. With the fiscal commitments he took on as part of his campaign, “sewer socialism” is likely even an exaggeration – his regime would’ve been significantly to the right of Bernie Sanders' mayorship of Burlington.

From here they jump to a glorification of the “Participative Councils” developed as part of Freixo’s campaign, effectively neighborhood branches of his political campaign, and tried propagandistically to swap them in and out for what they defended as the

creation of sovereign Popular Assemblies, with the election of representatives in every region, which have full powers to implement decisions and effectively control the budget and legislative power. Without advancing towards this, “it is not possible to govern”.[25]

A Constituent Assembly in One City? The MRT seemed convinced it could trick neighborhood campaign committees into becoming embryonic organs of some classless democratic control of the city. A utopian call for a democratic (not even socialist) sea of lemonade in the Bay of Rio de Janeiro.

However, as we know, Freixo is not anti-capitalist. He defends a series of progressive measures that we support and we will struggle for arm in arm, during the run-off and afterwards, but we want to say to everyone who is part of this great mobilization for Freixo: it’s necessary to go far beyond voting to advance in our struggle.[26]

They acknowledge that Freixo, and the PSOL, aren’t even anti-capitalist. However they will struggle side by side with Freixo for his “progressive measures” before and AFTER the election. They then invite everyone to become even better fighters for Freixo’s campaign by joining them.

Fortunately for the MRT and FT, Freixo lost. From 2020 onward the MRT remembered that Freixo was what he never stopped being: a bourgeois politician who wants more money for police.[27] In 2022 they concluded that he shouldn’t even be considered part of the left.[28] Careful, this bourgeois politician who isn’t even part of the left ran a campaign that is still enshrined by Albamonte and Maiello as the FT’s theoretical example of an alternative strategy to the neo-reformism of Syriza and Podemos. The Brazilian comrades may find themselves accused once again of being vulnerable to “Sectarian Degeneration”.

For anyone capable of searching back to the MRT’s 2016 position, their current denouncement seems incoherent. Freixo may be more comfortably embedded in bourgeois politics than before, but he’s only changed labels since 2016 when he was leading the construction of their potential “revolutionary fortress”.

Providing a framework of unity to this political incoherence is however the essence of the “strategic” perspective defended and advanced in Socialist Strategy and Military Art. The programs and principles upheld by Lenin and Trotsky will everywhere be minimized and pushed aside in favor of conceiving of them as the unique product of their “military genius”. What is behind this emphasis? They want to retrospectively transform the leaders of revolutionary marxism into what they themselves strive to become: all knowing “strategic” leaders who guide the party through centrist political zig-zags. The classic centrist sect which jumps from movement to movement, drawing militants into its wake and then bringing them into their closed social-political world to be commanded by the “military genius” of Albamonte and his disciples as they frantically zigzag left and right to gather “forces” wherever it seems most opportune.

In this way something completely unthinkable from the class politics of Lenin and Trotsky, an embrace of a perfectly bourgeois candidate like Marcelo Freixo who was obviously on the road to respectability, becomes a movement which “planted the possibility of an alternative course of rupture with capitalism, where the city would be transformed into a revolutionary bastion for the rest of the country”. The strategic genius of Albamonte-Maiello thought reveals it. Work in the United States within an auxiliary wing of the Democratic Party (DSA), the party of war and genocide as Left Voice has previously? Share the same party affiliation as capitalist politicians that vote to fund imperialist wars? Go ahead, it’s all about the great strategy of accumulating “forces'' for the revolutionary turn the leadership will give one day. Don’t hold your breath waiting though.

Clausewitz, Strategy and Program

Those who pick up the book looking for an introduction to the thought of Clausewitz will be disappointed. This is a book about the USE of Clausewitz both in its subject matter (debates within Marxism around Clausewitz and military theory) and its own destination (their use of Clausewitz to revise the Marxist program). It does not actually take the time to provide a significant summary of or balance of Clausewitz for the reader. On Clausewitz and the general concept of strategy, even within the left, most readers will find a bourgeois historian’s account like Lawrence Freedman’s On Strategy a far more effective introduction. In Albamonte and Maiello’s work they will find Clausewitz in cropped pieces, here and there, deployed to make a point or justify a balance. A dangerous use from the standpoint of comprehension as one of the main websites dedicated to Clausewitz legacy warns:

But regardless of which source you draw a quotation from, beware that any quotation, taken out of context, may not mean at all what you think it does. This is especially the case with Clausewitz, whose dialectical methods required the assertion of arguments that constituted useful propositions but were, in themselves, inadequate reflections of a useful understanding.[29]

Despite their pretensions, Albamonte and Maiello are far from the first to discover the influence of Clausewitz and to utilize him to rewrite the history of the Bolshevik Party. The British renegade from Trotskyism Tony Cliff in Lenin: Building the Party focused on the role of Clausewitz as well.[30] Tony Cliff in that series was seeking to consolidate the loose International Socialists into a more disciplined organization. Cliff painted a picture of a Lenin who was a strategic and tactical genius, who knew how to at just the right moments “Bend the Stick”, to overemphasize and tack to one or another side, in order to guide the Bolshevik Party ultimately to its victory. Cliff’s goal was of course a theoretical coat of point on a “Disciplined” Centrist organization which zig-zagged from movement to movement, picking up and discarding militants along the way and guided by a bureaucratic central leadership.

What Albamonte and Maiello propose after drawing a parallel between their “rediscovery” of Clausewitz and Lenin’s rediscovery of Hegel, is that:

It is not possible today to understand and much less to recover the legacy of Marxism developed by the Third International in its first years without understanding Clausewitz, and his appropriation by Lenin and Trotsky, which would continue through the Left Opposition and the foundation of the Fourth International. This is what we will take on in the following chapters of this book.[31]

Again despite claiming this, they do very little to provide a coherent, whole explanation of Clausewitz himself in the book. As a history of the USE of Clausewitz some of the very conclusions and analysis they develop contradict their own central claims. In particular in discussing and debating against the strategies of Protracted People's War in the Chinese and Vietnamese cases, as well as in Che’s Foquista concept, it becomes clear that Mao, Giap and Che themselves were clearly quite intimately familiar with Clausewitz. Indeed if a concept like “Military Genius” is to have any sense, Vietnam´s Vo Nguyen Giap certainly deserved it. Yet their limits flew from an incorrect understanding of class forces and other fundamentally POLITICAL, programmatic failures. Clausewitz did not and could not save them from Stalinism. So how can Clausewitz be our real guard against degeneration? Albamonte and Maiello advance the theory of Permanent Revolution as if it were a “Grand Strategy”. They do so thinking they are making Permanent Revolution something bigger, in reality they are stunting it and bringing it DOWN from the programmatic/political level.

Returning to the dictamen of Clausewitz that “War is the continuation of Politics by other means”, POLITICS is in command of war, that strategy and tactics serve as means for a PROGRAMMATIC foundation. This is why Trotsky at no point in his work constructing the Fourth International sought to focus on training cadres as “military geniuses” or set up a school of strategic mastery. If that were his intention we would surely have anecdotes of him sitting down James P Cannon and forcing the man to go through all of On War in his presence. Trotsky didn’t even have illusions as to his own military-strategic genius – the Red Army had better generals – he was a political and organizational commander. The core of his life was dedicated to laying the programmatic, political foundations of the Fourth Internationale. As Clausewitz himself explained, “If war is part of policy, policy will determine its character.”[32] Policy, in our case program, must drive our work and will ensure our victory – tactical or strategic “genius” could help or compliment these – but it can never substitute or take precedence. It exists as an extension of the former and subordinate to it.

What Albamonte and Maiello do is place military-strategic genius above and over the actual political programmatic foundations which should command them. They reverse Mao’s famous saying and construct an interpretation in which “the Gun commands the Party”. In doing so they abandon just that vital political and programmatic understanding which was conquered in the heroic years of the Third and Fourth International. By prioritizing strategy and tactics over program, they flip Clausewitz himself on his head. In doing so they free themselves up in the name of “strategy” to betray that programmatic foundation and open the road to new defeats for the international working class.

Debates in Social Democracy/vs Lih

We can see this distorted methodology from the beginning of their account of the debates in Social Democracy. The bulk of the first chapter focuses on the debates in the early German SDP around the strategy of attrition vs the strategy of overthrow as they related to the experience of 1905 in Russia. Albamonte and Maiello correctly polemicize with Lars Lih’s attempts to put a Kautskyite straightjacket on Lenin – something which in the US has served as the theoretical cover for a whole generation of pseudo-Trotskyist self-liquidation into the DSA.

The serious problem with their account, criticism and the lessons they draw are however that they effectively reduce the political and even strategic questions at stake to questions of the quality of the individual strategists. Kautsky was proven wrong by subsequent events, and so despite being well read on the subject and happy to utilize strategic citations in his arguments he lacked the qualities of “military genius”. Luxemburg engaged in an important political fight early, and so “she had no lack of ‘military genius’”,[33] but it was Kautsky and not Rosa who most thoroughly referenced their theory in military terms. Lenin and Trotsky’s character as “military geniuses” inspired by their appropriation of Clausewitz is the very foundation of the book, so we can take their labels for granted. Yet if Lenin’s serious appropriation of Clausewitz took place clearly in 1915; what relation did that have to the whole series of previous political and theoretical battles he waged to forge a Bolshevik party capable of rising to the heights of 1917?

There is a methodology at work here which is fundamentally at odds with actually extracting lessons from the debates and combat within international social democracy. What can we really conclude here? We need to be better strategists? But Kautsky studied and referenced more military strategy by far than Luxembourg, whose arguments were essentially political. Yet she was the better “military genius”. It’s a nebulous quality of leadership which is necessarily subjective, and can only be really determined years after the great political clashes involved.

Would reading Clausewitz have given Rosa Luxembourg and Karl Liebknecht the insight to form a revolutionary party earlier? Or to go into hiding before the 1919 massacre which struck down the German Party’s two greatest leaders? Clausewitz is a brilliant theorist-philosopher of War. More useful perhaps even than Machiavelli, or Thucydides and Sun Tzu, all of whom have useful insights for revolutionaries. It might have helped, but his military theory and strategy is not the universal key to unlocking the mysteries of revolutionary leadership. No more so than Hegel’s Science of Logic, which Lenin gave an even more thorough endorsement. From a historical materialist viewpoint in which revolutionary leadership is the question of seizing power in the imperialist epoch, our epoch – it could not possibly be such a guide.

What is the real “Center of Gravity” for revolutionary leadership? Above all it is in the political and programmatic foundations. It is not a Clausewitzian coat of paint thrown on the debates between Rosa, Kautsky, Lenin and Trotsky in the lead up to the Russian Revolution. It’s a thorough study of the organizational and political questions at stake and assimilating those political lessons. Those lessons as they are distilled programmatically and as they are expressed in the revolutionary continuity of the organizations and practice of the working class.

This is something that Albamonte and Maiello already begin to miss and misrepresent as early as these debates over the mass strike and German social democracy. They cite Rosa Luxemburg’s What Now? In which she polemicized against the Parliamentary Cretinism of the SDP and its turn focused on fighting the “Right”. It is a moment of Rosa frozen in time which is particularly convenient for Albamonte and Maiello where her more moderate intervention seeking to put the parliamentary posts at the service of the broader struggle lines up with how they like to envision their own use of the FIT-U in Argentina. Rosa in 1912 could not know that the Parliamentarians she wanted to fight for the 8 hour day, for a more aggressive working class politics, for using the parliament to strengthen the workers movement, were going to end up leading the most world-historic betrayal of the working class. The fact of 1914 changes one's attitude towards parliamentary work profoundly – not insignificantly it makes unity and propaganda blocks with pro-imperialist “socialists” (see the shameless support of the FIT-U’s MST and IS for US imperialism in Ukraine) completely unthinkable. Albamonte and Maiello want to dress up their own alliance with pro-imperialist parliamentary cretinism with a sprinkle of pre-war Rosa.

What was Rosa’s balance of parliamentary participation?

For real advocates of the revolution and of socialism, participation in the National Assembly today can have nothing in common with the customary traditional method of ‘exploiting parliament’ for so-called ‘positive gains’. We will not participate in the National Assembly in order to fall back into the old rut of parliamentarism, nor to apply minor corrective patches and cosmetics to the legislative bills, nor to ‘match forces’, nor to hold a review of our supporters, nor for any other reasons described in the well-known phraseology of the bourgeois-parliamentary treadmill and in the vocabulary of Haase and comrades.

Now we are in the middle of the revolution and the National Assembly is a counter-revolutionary stronghold erected against the revolutionary proletariat. The time has come, then, to assault and demolish this stronghold. The elections, the tribune of the National Assembly, must be utilized to mobilize the masses against the National Assembly and to rally them to the most exacting struggle. Our participation in the elections is necessary not in order to collaborate with the bourgeoisie and its shield-bearers in making laws, but to cast out the bourgeoisie and its shield-bearers from the temple, to storm the fortress of the counter-revolution, and to raise above it the victorious banner of the proletarian revolution.[34]

“Counter-revolutionary stronghold”, there’s some military terminology for the FT. It’s also an accurate description of the profoundly counter-revolutionary role which a “Constituent Assembly” played in the German Revolution, where it laid the basis for the recomposition of bourgeois rule under the Weimar Republic. For Rosa this embryonic parliament was a “counter-revolutionary stronghold” which we enter, and we do enter it, to “storm the fortress of the counter-revolution, and to raise above it the victorious banner of the proletarian revolution.” We do not enter to laugh it up with Maximo Kirchner or to accuse the representatives of the bourgeois of being “traitors”,[35] we explain that they are all loyal to their class. Because we are interested in tearing down the illusions of our class in its role, not building them up with fantastical appeals to a “Workers Government” of Tsipras or Freixo. You do not tear down a counter-revolutionary stronghold by telling everyone that it's actually capable of fulfilling revolutionary tasks.

Russian and German Revolutions

Stepping from the debates around Social-Democracy into the fundamental questions of organizing and winning insurrection there are no more important examples than the victorious Russian Revolution and the defeated German Revolution.

Albamonte and Maiello engage in a discussion over Trotsky’s theorization of the Civil War, relying on Trotsky’s Problem of Civil War as well as Nelson’s account of Trotsky as a military theorist. After discussing the strategy of presenting the insurrection as a defensive act with the Soviets, they go on to emphasize that:

The success of this maneuver demonstrated the “military genius” of Trotsky, as well as the whole October Revolution in Petrograd, an example of preparation and execution of an insurrectional offensive.[36]

A point which in isolation is indisputable, but contains the seed of a significant problem that will be revealed when they step on to the German terrain. They provide a useful summary of their analysis of the two revolutions in the crisis of the moment of the insurrection itself:

This is one of the moments of the greatest importance for the revolutionary party, since only an audacious and unyielding leadership, conscious of the pulse of the masses, can break with the old scheme and lead the movement to the seizure of power. In the Russian Revolution of 1917 the most decided sectors of the leadership imposed themselves, the wing of Lenin together with Trotsky, against Kamenev and Zinoviev who opposed the insurrection. In the German Revolution of 1923, for example, the conservative and wavering tendencies of the leadership triumphed, led by Brandler, and the insurrection was aborted. On the other hand, we also have cases of premature insurrections, where the “audacity” of the leadership did not match existing conditions, like the example of the “March Action in Germany in 1921. Or, as a positive example, the ‘containment of the premature insurrection of Petrograd in July 1917 by the Bolsheviks’.[37]

We will take up this conservative withdrawal, which Albamonte and Maiello acknowledge Trotsky argues emerges almost like a law itself – but they do not explore it in more depth. They have what is effectively an alternative explanation to this more political one advanced by Trotsky in his work on Civil War and in a series of later writings. As Albamonte and Maiello will summarize after they review the events leading up to the defeat in Germany:

As we will try to sketch out in this brief overview of the events, the KPD did not orient itself from a strategic viewpoint, and that is where we must find the causes of the defeat.[38]

The Russian Revolution triumphed in great part due to Trotsky’s possession of “military genius”, and the German Revolution failed centrally because the party did not have a “strategic” orientation, that is to say it lacked this character of “military genius”. That the German Revolution failed due in great part to a failure of revolutionary leadership is unquestionable – but the focus on “military genius” and the “strategic” element is subordinating the more fundamental political and programmatic elements at work. To understand this we should start with the explanations given by Trotsky which Albamonte and Maiello mention, but largely downplay in favor of this “strategic” orientation.

Trotsky in his work on Civil War that Albamonte and Maiello cite kicks off emphasizing again the primacy of politics around the question of Civil War:

We remain, therewith, in the sphere of revolutionary politics, for, after all, isn't insurrection the continuation of politics by other means?[39]

In line with this primacy of politics which Trotsky extracts from Clausewitz, when he addresses the failure of Germany he finds the foundation for it in fundamentally political causes:

However, there has been till very recently in the German Communist Party still a very strong current of revolutionary fatalism. The revolution is coming, it was said; it will bring the insurrection and power. As for the party, its role at this time is to make revolutionary agitation and await its outcome. Under such conditions, posing squarely the question of the timing of the insurrection means snatching the party from passivity and fatalism and bringing it face to face with the principal problems of revolution, namely, the conscious organization of the insurrection in order to drive the enemy from power.[40]

Trotsky prepared this text precisely as a guide and manual to explain, based on the victorious October revolution, the process of insurrection and political evolution of it. In this intervention his focus was on rendering clear the historical lessons which were the conquest of the Russian Revolution and the bitter harvest of the German defeat. There is no reference in it to “military genius”, and it could even be said as a criticism that it doesn't actually touch on the question of the party leadership – beyond mentioning the doubts which can surge within it similar to what happened with Kamenev and Zinoiev.

In a 1926 letter to Bordiga a, a revolutionary for whom Trotsky had tremendously more respect than Gramsci, Trotsky adds to this political analysis of the German failure:

One of the main experiences of the German insurrection was the fact that at the decisive moment, upon which, as I have said, the long-term outcome of the revolution depended, and in all the Communist Parties, a social democratic regression was, to a greater or lesser extent, inevitable. In our revolution, thanks to the whole past of the party and to the exemplary role played by Lenin, this regression was kept to a minimum; and this despite the fact that at certain moments the success of the party in the struggle was put into danger. It seemed to me, and seems all the more so now, that these social democratic regressions are unavoidable at decisive moments in the European Communist Parties, which are younger and less tempered. This point of view should enable us to evaluate the work of the party, its experience, its offensive, its retreats in all stages of the preparation for the seizure of power. By basing ourselves on this experience the leading cadres of the party can be selected.[41]

Social-Democratic retrogression is a considerably more refined political analysis which does not force us to rely on a nebulous concept of “military genius”. Rather it is a clearly defined political process which we can see directly has unfolded in most revolutionary workers parties who face a revolutionary situation.

Indeed it’s important when reviewing the German Revolution when so much emphasis is placed on the fight against ultra leftism, the failures of the 1919 Spartacist Uprising and the flaws of the 1921 March Action to remember that neither of those left or adventurist mistakes were what buried the revolutionary opportunity. Albamote and Maiello place the March action and the missed opportunity of 1923 on essentially equal planes, both failures of a leadership who were insufficiently “strategic”.

Even in defeat so long as it is not a decisive one, a failed uprising can raise the expectations of the class in the decisiveness and seriousness of the revolutionary party when a real opportunity emerges. In so far as there was a revolutionary opportunity in 1923 it was partly the consequence of precisely this process unfolding as an outcome of the failed, left putsches of 1921 and 1919. One social-democratic deviation in the decisive moment of the struggle for power however and the entire revolutionary opportunity can be buried for a whole period. The class can forgive those who fight too zealously in its name, but never those who desert the battlefield at the decisive moment.

This is also inherently a much more practical lesson: afterall how can we prepare for “military genius” or a “strategic orientation”? We can argue subjectively for far more than 600 pages what constitutes a good strategy. The danger of “social democratic regression” is much more actionable for a revolutionary organization and gives a clearer direction of march for the party. That within the party in the decisive moment it is likely that there will surge a Kamenev, a Zinoieve, a Brandt or… in the Italian case… an Antonio Gramsci.

Gramsci vs Trotsky

The Fraction Trotskista in their break from Trotskyism, far from seeking to guard against social-democratic regression, have built their theoretical innovations on the foundation laid by the great theoretical master of the “Social-Democratic regression”, Antonio Gramsci.

There is no more accurate way to define Gramsci and the general direction of his political thought. He was not, of course, the crass reformist who the latter day PCI and its academic sycophants turned him into. He was a communist, much like Zinoiev and Kamenev despite their own “social-democratic regressions”. Zinoiev’s loss of nerve in October didn’t prevent him from playing a decisive role of world-historic importance winning over the USPD against Martov in the famous Halle debate. Gramsci, subordinate to a revolutionary leadership, could have achieved great things – unfortunately he ended up subordinating himself to Zinoieve and the “Bolshevization” of the Comintern. As a leader, Gramsci’s regression in 1920 was an important element of the defeat of the Italian revolution. As Norden argued in another polemic with the FT on Gramsci:

Everyone, including spokesmen of the bourgeoisie, expected that the metal workers, with Gramsci’s Ordine Nuovo group at their head, would use the opportunity to strike the final blow. But no: although they had occupied the factories, they did not take to the streets to fight against the very weak police and military forces, they did not call on the railroad workers to go on general strike throughout Italy. In fact, they did not even stop production in those factories. Why not? Because in the Gramscian conception of factory councils, the point was to show the bosses, and the workers themselves, that they were capable of directing production. For Lenin and Trotsky and the young Communist International, in contrast, workers control was the prelude to insurrection. But neither in 1920 nor in his Notebooks did Gramsci concern himself with the preparation of workers insurrection. Instead, he fought to conquer hegemony in society.[42]

There is a significant parallel to be drawn here between Gramsci’s efforts to maintain workers control within bourgeois society, and the arguments advanced by Zinoieve and Kamenev on the eve of insurrection. As Trotsky recounted their arguments in his History of the Russian Revolution:

Before history, before the international proletariat, before the Russian revolution and the Russian working-class,” they wrote, “we have no right to stake the whole future at the present moment upon the card of armed insurrection.”

Their plan was to enter as a strong opposition party into the Constituent Assembly, which “in its revolutionary work can rely only upon the soviets.” Hence their formula: “Constituent Assembly and soviets – that, is, the combined type of state institution toward which we are travelling.” The Constituent Assembly where the Bolsheviks, it was assured, would be a minority, and the soviets where the Bolsheviks were a majority – that is, the organ of the bourgeoisie and the organ of the proletariat – were to be “combined” in a peaceful system of dual power. That had not succeeded even under the leadership of the Compromisers. How could it succeed when the soviets were Bolshevik?

“It is a profound historic error,” concluded Zinoviev and Kamenev, “to pose the question of the transfer of power to the proletarian party – either now or at any time. No, the party of the proletariat will grow, its programme will become clear to broader and broader masses.[43]

Gramsci’s position in the face of the revolutionary events of the Biennio Rossi was not that different from Zinoviev and Kamenev – replace “Constituent Assembly and Soviets” for “Workers Control and the Bourgeois State”. One could easily imagine in the aftermath of a missed opportunity for the Russian Revolution, Zinoieve or Kamenev going on to write voluminous tomes about how much more was needed, culturally, politically, industrially, for there to have been a victorious Russian Revolution. Thankfully Lenin and Trotsky’s decisive battle for the insurrection gave us the world’s first workers state and spared us from a bleak future of Zinoievite and Kamenevite academics.

Albamonte and Maiello attempt to wield together a supposed “convergence” between Trotsky and Gramsci around the Lyon Thesis. It is a deeply dishonest attempt which could only be made under the assumption of almost total ignorance among the readers as to the purpose of the Lyon Thesis, the state of the Comintern and the battles within the Italian Communist Party of that time.

Albamonte and Maiello talk about the Lyon Thesis as if it were some independent intellectual investigation, some doctoral thesis of Gramsci in which the embryos of his real thought can be found, “un documento fundamental en su pensamiento maduro”.[44] It was a party document which applied the prevailing, Zinovievite Comintern orthodoxy of 1926 to the conditions of Italy. Its central aim was to sideline Bordiga’s left faction and install the “Bolshevization” of the party as one commanded bureaucratically and totally subordinate to Moscow. It was cowritten with Togliatti, the great betrayer of the Italian working class who guaranteed the world-historic capitulation of the PCI after WWII. A fact Albamonte and Maiello must know but choose to exclude from the record.

What did Trotsky have to say about Togliatti (Ercoli)?

The barren casuistry of his speeches is always directed in the last analysis to the defense of opportunism, representing the diametric opposite to the living, muscular and full-blooded revolutionary thought of Amadeo Bordiga. Wasn’t it Ercoli, by the way, who tried to adapt to Italy the idea of the “democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and the peasantry” in the form of a slogan for an Italian Constitutional Assembly, resting on “workers and peasants assemblies?”[45]

That is Trotsky’s verdict on the coauthor of the Lyon Thesis, and his defense of the counterposed “muscular and full-blooded revolutionary thought of Amadeo Bordiga”. How could this document possibly be the source of “convergences” between Trotsky and Togliatti’s co-conspirator, Gramsci? Yet this is in truth only the beginnings of the problems with the Lyon Thesis, based on interpreting it textually rather than understanding its context within the Italian Communist Party. The Lyon Thesis was the culmination of a historic crime against the international working class which laid the foundations for the betrayal by Togliatti 20 years later.

An extensive treatment of Bordiga and the Sinistra, the left within the Italian Socialist Party is beyond the scope of this work. The demonization of Bordiga went hand in hand with the cult of Gramsci with which the post-war PCI consecrated its historic betrayal of the working class – much of this demonization has passed on to non-party historians and academics who absorbed it. It is worth restating that Bordiga was one of the few figures of international social democracy to call for a consequential struggle against the war, that he held the loyalty of an overwhelmingly militant, working class base of the Sinistra and PCI. There are few figures for whom Trotsky and Lenin held more respect – this does not and should not minimize political differences – but Bordiga in this period was a leader elevated by the most militant vanguard of the Italian working class and who held their loyalty in a manner comparable within the International to Lenin, Liebknecht, Luxembourg and Trotsky.

Gramsci had no such history or base and relied overwhelmingly on the backing of the Stalinizing Comintern. The sordid details of Gramsci’s campaign in the lead up to the Lyon Thesis are told in masterful detail by John Chiaradia in Amadeo Bordiga and the Myth of Antonio Gramsci.[46] It begins with Gramsci being appointed by the Comintern in 1924 as the “General Secretary” of the Italian Party, an entirely new post for the party. Gramsci, based essentially around the group of petty-bourgeois intellectuals of New Order, together with Togliatti and other Comintern agents launched a campaign to wrest the party from Bordiga’s working class supporters.

This campaign reached its height at the same time as the anti-Trotsky campaign in the USSR did, after the publication of Trotksy’s Lessons of October. Bordiga wrote an article in defense of Lessons of October[47] and was prevented from publishing this in the PCI paper. For the Gramsci-Togliatti center, this became a useful point to link the struggles against Bordigism and Trotskyism. However, even slanderous political methods were unable to break the loyalty of the PCI’s worker militants to the left.

A vicious campaign of abuse and bureaucratic diktats was launched aimed at cutting down the overwhelming radical, working class base of the PCI which supported Bordiga. Within the Comintern only the struggle within the Soviet Party itself against Trotsky is comparable. Open censorship blocked any effective written responses. At the organizational level there was the enforced adoption of cell based structures that – effectively – isolated worker militants from the broader political discussion.

In the lead up to the 1926 conference that produced the Lyon Thesis, this saw entire city branches effectively disaffiliated in order to build “loyal” groups from scratch. Gramsci established a 90.8% majority which was mathematically and politically impossible to achieve in an honest way. Any “abstaining” (under conditions of fascism!) Sinistra member who didn’t vote otherwise was considered a vote for Gramsci’s center. Provincial conferences were held and where Bordiga’s wing easily carried the discussions, it was of course considered unnecessary to vote or hold any resolutions.

The results on the PCI’s militancy and its working class base were of course devastating. “Party membership in the industrial centers typified by Turin and Milan had halved in the period 1925-1926”.[48]

This vicious, demoralizing and destructive campaign was carried out throughout 1924-26 under the conditions of Fascism, of the move by Mussolini to consolidate his power which would result in both Gramsci and Bordiga being arrested. Bordiga was stripped of his staff position and was forced to look for work! The Italian Left was sidelined in a moment where openly organizing a political alternative was almost impossible! The best, most serious militants capable of taking on underground work were isolated or disaffiliated. Whatever differences there may have been with Bordiga around the United Front, it is nothing compared to the work of demoralizing, deaffiliating and burying the working class base of the PCI. Gramsci was responsible for turning the most important vanguard organization of the Italian working class into a lifeless husk.

In the face of this vicious campaign, where there was a real “convergence” between Trotsky and a major Italian Communist in 1926 it was between Trotsky and Bordiga. In a Letter available on the PTS own theoretical website[49] Trotsky in reference to a 1925 document (not 1926 as he writes it) declares: “The Platform of the Left (1926) produced a great impression on me. I think that it is one of the best documents published by the international opposition, which preserves its significance in many things to this very day.”

This Platform of the Left is in fact the Platform of the Committee of Intesa[50], a key document grouping together the left opposition to Gramsci and Togliatti’s Bolshevization of the PCI. It is important to clarify that Trotsky followed up this correspondence with more critical remarks which, while still endorsing the 1925 document for its time, argued that it did not provide sufficient answers for the situation of 1930. Trotsky had a falling out with Bordiga’s followers even as he retained considerable respect for Bordiga himself.

However, given that Albamonte and Maiello are attempting to make the Lyon Thesis the bridge with which to connect Trotsky and Gramsci, Trotsky’s open endorsement of a document against which the Lyon Thesis was directed is impossible to ignore.

All this is not to brush over Bordiga’s real political divergences with Trotsky and Trotskyism, but the fact is in the face of the degeneration of the Comintern, the most important issue of the time, Bordiga had the political instincts and understanding to be on the right side. On the stage of revolutionary class leadership rather than academic citation count, Bordiga was a giant compared to Gramsci.

These issues are even on display in the recorded discussion (after the organizational crimes had been committed) around the Lyon Thesis itself by Gramsci, Togliatti, Bordiga and others. As the record shows, Gramsci “Advances a historical justification of the value of the process of "Bolshevization" of the proletarian parties that was begun after the Fifth World Congress and the Enlarged Executive meeting of April 1925”.[52] Indeed Gramsci goes much further and adopts directly Stalinist arguments: “Comrade Naples has protested against the way in which the campaign against the far left's factionalism has been conducted. I maintain that this campaign was fully justified. It was I who wrote that to create a faction in the Communist Party, in our present situation, was to act as agent provocateurs, and I still stand by that assertion today.”[53] Accusing the left of being agent provocateurs, police agents, is about as deep an embrace of Stalinism as was possible. From an “agent provocateur” of Mussolini’s Italy we are only a short conceptual ride away from the “Trotskyite-Zinoievite terrorist center”.

Bordiga by contrast argued against Gramsci that “The system followed in creating leaderships for the individual parties is incorrect, as is the system whereby discussions for the World Congresses are imposed and directed. In this field. we accept the criticisms formulated by Trotsky of the International's method of work.”[54]

Gramsci’s Letter to the Central Committee of the Soviet Communist Party makes his support of Stalin against the United Opposition amply clear. His appeals to Unity in the party line up more or less perfectly with that of the capitulations of Zinoieve and Kamenev to Stalinism. This direct stance against Trotskyism was, alongside the ambiguity of his writings under prison censorship, the foundation that was necessary for the later day Reformist PCI to make him the chief intellectual base of their own reformist turns and build Gramsci into an academic idol. Anti-Trotskyism was and remains today a fundamental requisite for academic prestige. A limit the bourgeois state imposes on efforts to grasp “cultural hegemony”.

From the totally subordinated Stalinist structure implemented in the PCI by Gramsci and Togliatti, we are only a short nod from Moscow away from Togliatti’s ultimate betrayal of the Italian Working Class. Albamonte and Maiello will go on extensively about the supposed “Order of Yalta” and its role in burying the post-war revolution. Yet none of this would have been possible in Italy without Gramsci’s tireless bureaucratic work culminating in the Lyon Thesis which they so value.

Bordiga’s final political destination lay far away from Trotskyism – but his destination was also tied intrinsically with that path that brought him there. It is impossible to speculate too deeply on what a PCI driven by the radical working class base of Bordiga would have or could have done – if it would have been up to the challenge of the post-war struggle for power or not. We can never know, because Gramsci together with the Stalinized Comintern destroyed the Italian Communist Party as it was. The Lyon Thesis was the gravestone that marked the death of this once vibrant radical working class organization. The re-appropriation of the Lyon Thesis by self-proclaimed “Trotskyists” is nothing less than grotesque.

Gramsci and Democratic Demands

What exactly are Albamonte and Maiello attempting to establish with these supposed “convergences” between Trotsky and Gramsci rooted in the Lyon Thesis? Afterall even in most of the comparisons they develop throughout the book, Trotsky comes off as having a superior understanding of the conjuncture and fundamental political questions of the epoch (the role of the bureaucracy, united vs popular front, etc.). Reading it one can’t help but be struck by the impression it is an effort to sell Gramscian academics on the value of Trotsky, rather than to explain the value Gramsci offers to a revolutionary workers party.

In their earlier theoretical article on the subject, they focused on the value of Gramsci’s concept of passive revolutions for understanding the post-WWII boom, both from the capitalist side of US domination and economic growth, as well as from the side of “proletarian passive revolutions” with the establishment of the Deformed Workers States.[55] This formulation conceals an essential process in the creation of those Deformed Workers States – the smashing by the Red Army of the old capitalist state. A concept of “Proletarian Passive Revolution” skips over this vital component and can easily lead to deep confusion as it does for the FT. Rather than a parallel with late Nineteenth century Italy, the more correct parallel is to be drawn with those bourgeois states established in the wake of Napoleon’s Grande Army as it tore down the old feudal structures in its wake. A march that also had its counter-revolutionary components – most notably Napoleon’s attempt to reconquer and restore slavery in revolutionary Haiti. This is a historic parallel already founded in Trotsky’s analysis of a Soviet Thermidor and Soviet Bonapartism.

What Albamonte and Maiello here attempt to wring out of the Lyon Thesis and the rest of these “convergences” is a justification for a series of “radical democratic” demands. They use an article from 1931 by Trotsky on Spain and then link it to the Lyon Thesis, making the latter out to be a precursor of permanent revolution!

The “Thesis…” planted the impossibility of an “intermediate” democratic revolution in the face of fascism and characterized that what was ahead was the socialist revolution, coinciding in fact with this aspect of Trotsky, which had sustained the theory-program on the permanent revolution for Russia.[56]

So apparently, Togliatti signed on to a document that endorsed the permanent revolution? A document which was the culmination of a campaign waged against a Left which had defended against Gramsci and Togliatti Trotsky’s Lessons of October? How fortunate for him that no-one let Stalin know about it during his extended stay in the USSR…

Of course defending the formal perspective of socialist revolution in Italy, an advanced capitalist country, was largely Communist orthodoxy right up to the Popular Front. In the context of a party campaign against a militant workers left, maintaining this was essential. The United Anti-Imperialist Front and the perspective of a democratic revolution first then applied only to semi-colonial countries. By Albamonte and Maiello’s logic we can talk about “convergences” between the Permanent Revolution and 90% of the Stalinist Comintern right up to the period of the Popular Front. Something which should highlight just how tenuous all these supposed “convergences” are and just how important the fundamental differences were.

We have at this point amply demonstrated the bankruptcy of “convergences” between Trotsky and the Lyon Thesis, so let’s focus directly on the political objective, the ultimate destination at which the FT wants to arrive as they summarize themselves:

In this sense, what we have attempted to show are the roads and tools with which to struggle for that hegemony, necessarily “anti-regime”, which were sustained by Lenin. Taking from Gramsci his developments and his productivity in analyzing the processes of aggregation and disaggregation of classes through which the bourgeoisie maintains its hegemony, alongside the precise tactical and strategic articulation of Trotsky. A vision which escapes from the economist caricatures of “permanent catastrophe” and of masses always located 180 degrees from their leadership. From here the role of democratic-radical demands, vital to avoid both assimilation by the regime and sectarian impotence; the articulation of the united front and the struggle (in politics and unions) against the bureaucracy; the fight against the “democratic” parties of the petty-bourgeoisie to conquer hegemony over the middle sectors; the articulation of these elements with the development of the offensive united front (soviets) and the workers government, in the anti-bourgeois and anti-capitalist sense which Trotsky emphasized against the popular fronts.[57]

Assimilation of a Gramscian rather than Leninist conception of hegemony opens a dangerous road towards opportunism – one which historically tends to take parties out of the factories and into graduate seminars – resulting in rambling discussions about Foucault. A full polemic against Gramsci’s views on hegemony is out of scope, but we can pose a simple question. When have Gramscian concepts actually served as an effective lever of revolutionary theory and action, rather than an effective way to pad academic resumes and sweep up grant funding?